Talking to Sebastian Dieguez

Under the Sea, Under the Sea

Under the Sea, Under the Sea

(Dieguez desperately fighting for his world-view paradigms...)

Under the Sea, Under the Sea

Under the Sea, Under the Sea

Ok, I decided to make my brief comments in the whole of

Dieguez reply to ST (run by Jime Sayaka). My comments in blue (note that

I have removed the hyperlinks from the original text)

Subversive

Thinking responded (some

time ago) to my comments on his critique

of my review (of which some words here) of Irreducible

Mind. I will in turn answer to it, quite at length, but first I want

to thank ST for his time and say sorry if I even minimally hurt or shocked

him in any way. Personnally, I don't mind about irony and sarcasm at all

in a discussion, I'm more annoyed by sanctimony, self-righteousness, whining

and boring people altogether. But more on this later. Ok, so now to the

lion's pit. I write in black, Subversive Thinking's comments are indented

and red (warning, this is the reverse from the previous post, sorry for

the inconsistency but that was just easier), external quotes are in green.

I explained

in my review and in my first comments that IM's argument amounts to a

"soul of the gaps" (i.e. the "transmission" hypothesis of mind-brain relationships).

Note, Sebastian, that the logic from the authors here is

that a soul fits in the gaps, but many other alternative “theories” do

not fit in it. That is why this is not precise to label this approach from

them as a soul of the gaps. When we talk of soul of the gaps or God of

the gaps we are referring to something different. We are saying this: “Hey,

this does not have an explanation, so God may be the cause.” Borrowing an

example from this very discussion but using it according to my logic: “Spontaneous

cancer remission has no cause that I know of, therefore it was God that

miraculously cured my friend from his cancer!” Note that in this situation

there is no pattern that leads you to prefer God over alternative theories.

You are making this choice based on faith. But imagine this other (hypothetical)

scenario: “Gosh, these innumerable and fantastic advanced physic’s equations

are coming out of nowhere on the screen of my computer; they are hundreds

of years advanced from what we know. It must be coming from some god-like

intelligence out there!” (remember the movie “Contact”, after the book

by Carl Sagan?). In this example we have a pattern that helps us in trying

to create a “theory” to explain the phenomenon. IM is closer to this last

example (though the authors’ conclusions and theory may be wrong).

ST insists

that this particular “theory” is a logical "conclusion" from the available

data, and not an "assumption" at all.

Sorry, I ended up adding to the “lots of repetitions” and

“more of the same”… :-)

This is

like saying that Intelligent Design is a logical conclusion from the available

data.

And actually it is…! You can take it from me. I am a biologist

who has thought it over lengthily, and who has read a lot from the contending

parties on this matter. But this has to be further elaborated (and expect

nothing more than strict mainstream evolutionary thinking from me on this

matter).

Sorry,

but no, dualism in any of its forms (and “transmission” is certainly a brand

of dualism)

I am not really trying to dwell on that PhD student stuff.

But anyway, I like to share viewpoints regarding proper attitude and remarks

and not proper attitude/remarks. Do not see that, please, so much as

preaching, but rather as an exchange of viewpoints. You said above, “any

of its forms.” Some people say, and I agree, that scientists (at least

while they are trying to behave as scientists) should avoid words that

convey totality. There is a nice phrase that says “Always and never are

two words you should always remember never to say.” Alongside this, I have

heard more than once (and I agree) that “true scientists speak in probabilities”

(instead from in yes and no).

does simply

not follow from what one finds in IM. A “transmission” theory of

mind-brain relationships simply needlessly multiplies the number of entities

necessary to make sense of the data.

You see, monism, dualism, and pluralism are concepts that

keep coming and going throughout the history of human thought. IMHO, these

concepts are not to be despised. Instead, we should look at them with

respect, care and wisdom. They all have kernels of truth in them (IMO).

And especially neuroscientists should be quite welcoming towards the idea

of multiplication of entities. Have you, Sebastian, ever entered consciously

into your dreams and tried to talk to the dream people from your very

own mind? Well, I have (and also many other people have too). And what

we find in us is truly amazing, and far from “unitary” (monistic).

Consider

an example: either people or aliens are responsible for a particular crop-circle,

it does not help at all to put forward the possibility that aliens are

remotely controlling enslaved human beings to make crop circles from outer

space.

Why are you doing away with aliens, to begin with? If you

show that child prodigies are explainable through present-day neurological

knowledge, then this specific phenomenon ceases to require an alternative

explanation (be it dualistic, demonical, etc). That is the point. That

is what I meant when I replied to Jime at the link below:

http://www.criticandokardec.com.br/irreducible_mind.htm

I said: “At a preliminary reflection, I think only survival

seems necessarily to outstrip the potential powers of the body.” What

I meant was that I actually saw very little “irreducibility” in what the

authors presented. Even psi (say, telepathy) may exist and yet be reduced

to ordinary well-known neurology.

At any

rate, as long as “transmission” remains such a poorly elaborated alternative

to materialism, then one is allowed to adopt any other indeterminate

guesswork about how the universe works (divine intervention, an alien trickster,

magic wand-like super ESP, and so forth). All of this is utterly unwarranted

if one is serious about making scientific progress.

The authors

of IM follow Myers in his strategy of building a "bundle" of converging

evidence, assuming like him that there is a continuum of normal, unusual

and psychical phenomena that suggests a stratified view of the human mind,

each layer sort of producing its own phenomena depending on the more of

less "permeability" of hidden forces, or something. But this is entirely

artificial,

there is

no obvious reason why stigmata, the placebo effect, genius, NDEs and mystical

experiences should all point to the same conclusion, even if there

were anything genuinely paranormal about them (which is precisely the

question at stake).

Anyway,

I’m not here to re-review this book. So let’s take ST’s comments one by

one. After making much of my alleged confusion between “assumption” and

“conclusion”, he writes:

Dieguez

fails to discern between knowing the existence of a fact and knowing the

explanation for a fact. This conflating is astonishing in a PhD. student.

See what

I mean when I say sanctimonious and boring? This “PhD” thing will come

up several times in the discussion, so let me say right away to ST that

I like discussion and dialogue (vigorous or not), but I don’t take lessons

from complete strangers about the moral and scientific standards a PhD

student should hold. If ST doesn’t have a PhD, then I suggest he tries

to obtain one so that he can put his particular standards to good use. If

he already has one or is doing one, then good for him, he must be proud

and very serious about it.

In any

case, what he’s doing here is transparent: he simply says that everything

that is described in IM are facts, but because not all of them have

an explanation, then I simply prefer to ignore them. That’s must be because

I’m stubborn, ignorant, and fearful of change. Well, I don’t buy this rhetoric

and I dislike it. So let me repeat: the paranormal aspects described in

IM (veridical perceptions during NDEs, mediumship, apparitions, ESP in

general, etc.), are not facts, have not been established as facts, and

do not seem to be in any progress of being accepted as facts anytime soon.

Therefore,

what needs to be explained, is what is going on with the persons who report

such things, the scientists who claim to have observed them and the persons

who believe them. This might be ultimately misguided, but it is a reasonable

and parsimonious approach (and even the only one who can actually help

establish the paranormal as real).

Then he

goes on to provide examples of things that exist but that have no explanation:

-Consciousness

is known (by introspection), but nobody has presented any adequate model

to explain how on earth matter produces it. That is, we don't have an explanation

for consciousness.

-Spontaneous

remission of cancer is a known (and infrequent) clinical fact. But no one

knows the explanation for such fact (and there is not oncological theory

that predicts it, because cancer is considered a progressive fatal disease

if left untreated).

-The

placebo effect is a well known fact in medicine, but no adequate explanation

for it exists. In fact, given that the placebo effect is, by definition,

caused by the belief of patients (and therefore, by their subjectivity)

some materialists have tried to dismiss it.

Well, I humbly kind of disagree from the "examples" above.

First, I agree with consciousness, even though this has to be more elaborated.

But spontaneous remission of cancer and placebo effect are most likely

pretty much explainable through conventional science. In both cases, the

action of the so called neuro-immune-endocrine system is most likely

at play.

He could

go on and on actually. Nothing in the universe is completely explained.

That’s

not how science works. But let’s take these examples in turn. I think that

consciousness does exist, but only insofar as intelligence, jealousy or

patriotism also exist. These are bad examples of what one would consider

a “fact”. First, you have to go through the trouble of defining consciousness,

otherwise you might as well claim that the soul exists through introspection.

But more importantly, this definition will inevitably color your assessment

of the neuroscientific data. Some views of consciousness simply beg the

question by stating right off that it will never be explained by science.

I’m not

interested in such an approach. I was at the latest Association for the

Scientific Study of Consciousness in Berlin (13th ASSC), and

believe me, people are working hard on this topic and making progress on

many fronts. Now, the scientific study of consciousness is very recent in

the history of science, and there is still a long way to go.

But even

so, it is encouraging to compare the results and progress of cognitive

neuroscience in this area to that of psychical research and parapsychology,

which have been at it for more than a century. You only have to learn a

little bit about what happens in the brain during binocular rivalry, backward

masking, synaesthesia, blindsight, hallucinations and so forth. We do

know a lot. The phenomena I just listed have been unambiguously established

and are beginning to be explained. Can you say with a straight face that

ESP and survival have been established in the same way?

Then there

is the example of spontaneous remission of cancer. Think of the differences

with the previous example. This is something altogether different: what

counts as “spontaneous”, what counts as “remission” and what type of “cancer”

exactly? How big is the pool of such events to allow for systematic research?

What type of explanations has been previously advanced? Etc. I’m not going

to do the homework now, this is not my field, but I’m unimpressed by the

comparison of this example to, say, the reality of distant healing through

prayer (as unashamedly discussed in IM).

Then there’s

the placebo effect, which is also discussed in IM, as if somehow this

interesting phenomenon should lead one to believe in dualism or survival.

The topic has been a hot one in medical science for the last 15 years or

so. There are tons of research and reviews on the topic. There are many

issues of definition, methodology, interpretation etc., but it is certainly

false to say that “materialists” dismiss it. Otherwise, why should literally

every study conducted by materialist medical scientists include

a “placebo” group?

So there

you go, three very bad examples to distract one from the only problem

we are dealing with: please establish ESP, veridical perceptions during

OBEs-NDEs and communications from the deceased as facts, and then

look for an explanation.

I do have

a problem with the arrogance of IM in dismissing the successes and constant

progress of cognitive science

without

proposing a clear and testable alternative.

But this

is not my main concern. My main concern is that any such alternative theory

is not warranted,

because

the paranormal as not been established

and the

real world behaves exactly as if there was no paranormal in the

first place.

I am reminded

here of a 70’s picture showing Uri Geller covered by electrodes and measuring

machines at SRI, as if the explanation of fraud and chutzpah was to be

found in his physiology.

The example

of the placebo effect is immediately followed by this gem:

(oops, that is another gem...

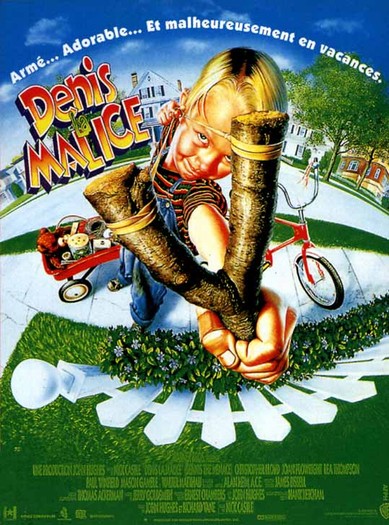

(oops, that is another gem... ![]() )

)

That

"the mind can affect the body's biochemistry" is what we'd expected

IF dualism is true.

I couldn't

disagree more. Why does ST think that dualism is overwhelmingly rejected

by scientists? He surely must realize that the main problem with dualism

is precisely the lack of explanation for how "the mind can affect the body's

biochemistry". By definition, this problem does not exist for materialism:

it is simply a thing we must study carefully. You see, if the “mind” really

is nothing but brain processes, then its effect on the body’s chemistry

is not such a big problem after all. But then, I’m only being a rude PhD

student, what do I know.

So,

Dieguez's argument, if applied consistently, would be useful to refute

and dismiss much of the data accepted by mainstream science. His argument

that an explanation is needed would serve to dismiss spontaneous remission

of cancer or consciousness. His argument that the data is controversial

would serve to refute consciousness too (since there is controversy about

if consciousness exists at all, as argued by some eliminative materialists

and even by Dieguez who consider it an illusion of the brain)

This is

nonsense. I’m not the one suggesting that one should look for a

miraculous and revolutionary non-materialist approach to consciousness,

spontaneous remission of cancer or the placebo effect. Persons like ST and

the authors of IM are. Because these are gaps in our full

understanding of the material world, they jump to the conclusion of the

“soul of the gaps” (so one is left with a choice to make: either “promissory

materialism” or “the soul of the gaps”: take your bets).

And I want

to say something about the use ST makes of the notion of “controversy”

here. Consciousness research is controversial in the same sense that there

is controversy in any field of science (evolution, physics, animal behaviour,

sociology…). That type of controversy is good and scientists just love

it, it allows them to compete against each other and therefore accelerate

progress. The mistake comes perhaps from also calling such things

as parapsychology and creationism “controversial”. This is too weak a word.

These things should better be qualified as “esoteric”, “stupid”, “nonexistent”

or “false”. This should go without saying, but then believers are convinced

that research on ESP and research on consciousness somehow stand on the

same ground. This obviously leads to many misunderstandings, so here I brought

two simple examples : (i) Uri Geller claims (or claimed) to bend spoons

with the power of his mind alone, (ii) there exist some accounts of levitation.

So, should we try to confirm scientifically these observations,

or right away bring our measurement devices to try to explain how

such feats are done? If you don’t do the job to the satisfaction of all

parties, if then you nevertheless claim that these “observations” disprove

“materialism”, and if eventually you argue that there must be a better

explanation but then merely say something vague about the soul or whatever,

then you have effectively established yourself as a crackpot. The examples

and comments of ST are irrelevant here. Before you try to explain something,

there has to be a something.

In the

following sentence, ST thinks he caught me in a blatant demonstration of

bias.

Thus,

Dieguez doesn't reject paranormal phenomena due to a lack of explanation

or a lack of a theory for it, but because it's inconsistent with materialism.

And this point was explicitly conceded by Dieguez in this comment in Michael Prescott's blog: "Materialism has not been destroyed by the

cross-correspondences or by NDEs, because materialism is simply unaffected

by the multiplication of GHOST STORIES"

(Note how Dieguez conflates paranormal evidence with ghosts, conflating a

genus with its species. An amazing and inexcusable intellectual, logical

and conceptual confusion for a Ph.D student!. In fact, such a deficient comment

suffices to avoid further debate with Dieguez but, seeing as this an interesting

topic, I'll continue with my reply)

Read that

sentence in green again, it is not a "concession" of any kind, that’s

simply a truism. I don't know what is controversial here: materialism,

taken as the ongoing activity of scientists in the world, physicists, biochemists,

neuroscientists and so forth, works just fine and is unaffected

by reports of NDEs and trances of automatists. Or else just try asking

any living scientist ("mainstream scientist", if you want, not Radin, Schwartz

or Sheldrake) if she ever tried to reconcile her findings with the existing

data on Mrs Piper’s mediumship, for instance, or if she merely felt there

was any need to do so in the first place. I realize this is a disturbing

observation for someone who really believe in the paranormal, but it is

uncontroversial that science works just fine without taking psychical science

and parapsychology seriously. Day after day, week after week. It is not

only that parapsychology and psychical research have not and do not hurt

« mainstream » science in any way, but more generally that given the current

state of knowledge, the progress made has been so enormous and thrilling

that it simply would be stupid to turn everything upside-down merely on the

basis of dubious "evidence" (i.e. GHOST STORIES).

I know,

like Prescott, ST is shocked by my use of the term GHOST STORIES (which

I write in all caps, yes). ST chastises me for confounding "paranormal

evidence" with "ghosts". This is "conflating a genus with its species"

he says, and (again) this is inexcusable behavior for a PhD student. Maybe

ST is totally unable to read between the lines, or he is utterly impervious

to any sense of humor, but the relevant thing here is not my alleged sloppiness

in basic logic. The question remains: does ST actually believe

in ghosts? If ST believes in apparitions, hauntings, mediumship, and poltergeists,

then yes, he believes in GHOST STORIES. I personally don’t, but go figure,

I’m just a misbehaving PhD student.

Ok. Now that we know who he is, let's proceed.

He follows

by quoting how I characterize the transmission hypothesis as an argument

from ignorance, and he writes this:

False.

An argument from ignorance consists in concluding X in the absence of

the evidence for or against X.

ST doesn’t

know what an argument from ignorance and/or from incredulity is. One can

find different definitions of these fallacies, but what he says is not

one of them. The version I was talking about is the most widespread one,

I think, and it only demands that you replace “in the absence of” by “because

of the absence, or perceived absence of” in ST’s definition above. But

I don’t want to be too blunt here, after all ST, as far as I know, might

not even be a PhD student.

What follows,

sadly, is more of the same:

But

the authors [of IM] are not concluding from the absence of evidence, but

from the POSITIVE evidence in favor of X (e.g. paranormal evidence). If

you dispute the evidence for X, then there is a debate; but controversial

evidence is not the same that the total absence of evidence.

Dieguez

conflates controversy about the evidence for X, with the absence of evidence

for X. Another logical and conceptual mistake.

ST seems

to follow the teachings of creationists. He takes advantage of the ambiguous

notion of “controversy” (see above). We could go on for hours, but none

of the claims of parapsychology has been established. None. On the other

hand, fraud, misobservation, misreporting, wishful-thinking and methodological

sloppiness do exist, and happen to be fairly well represented throughout

the history of psychical research and parapsychology (how come? One wonders).

It’s actually

all the same since Myers (at least): pick up GHOST STORIES and tons of very

sloppy and bad research, mixed it up with interesting but irrelevant medical

wonders that are not ostensibly paranormal at all, and claim that you have

made a big bundle with all of this.

Each stick

of the bundle is weak, but the bundle itself is strong.

Well, I

don’t find this argument persuasive. In fact, I find it hilarious. (I know,

laughter and mockery are not appropriate behaviours for a PhD student). I

have a better metaphor for the sum of paranormal “evidence”: it’s not a

bundle, but a house of cards. Only the cards are a wild assortment coming

from very different decks, and for the moment they are merely scattered around

the floor.

By the

way, this whole usage of mine of the term GHOST STORIES is not purely idiosyncratic

(except for the caps). It was acknowledged by Trevor Hamilton in his biography

of Fred Myers. It took me a while to find out where I had read that precious

quote, but here it is, from p.194 of Immortal Longings [this follows

from a remark about the fact that some persons, including Emily Kelly,

were surprised upon first reading Human Personality to find out

that there was little discussion of survival per se in there, and much

about all kinds of abnormal psychology]:

“Myers,

in fact, decided that he would have to address wider issues [than merely

survival], including the mind-body problem and human abnormal psychology,

as well as the results of research into mediums, if he was to develop a

satisfactory and persuasive theoretical framework to which others might

give, at least, provisional assent or interest. Otherwise, his and the

Society’s work would be treated as just a better written and better evidenced

set of Ghost Stories than those of the past” (my emphasis,

please note the use of capitals in Ghost Stories by Hamilton).

Indeed,

that was perhaps bound to happen, even with the presence of psychological

mysteries in the book (and these stories are actually not better

written, and perhaps not even better evidenced, than those one can find,

for example, in the recently reissued Oxford Book of Ghost Stories

edited by Cox and Gilbert, OUP 2008).

ST then

writes:

Since

Dieguez is so "evidence-based", I challenge him to provide evidence for

his claim that "the authors never tire of saying that everybody is wrong

except them". I await this evidence.

But IM

is entirely written in this vein. That’s the main point of the book,

to challenge “current mainstream neuroscience”. Now, cognitive neuroscience

is a huge enterprise, with thousands of scientists around the world working

hard and publishing tons of papers in dozens of specialized journals. If

all these persons simply don’t take into account the insights of Bergson,

James, Myers and Kelly et al. about mind-brain relationships, then IM is

effectively saying all along that everybody is wrong except them (plus

a few others, of course, one should not forget about Mario Beauregard and

the deluded Denyse O’Leary, which ST obligingly interviewed for his blog).

Let me also reprint here the quote that ST himself has conveniently

taken from IM in his previous post about my review:

“The

authors of this book are united in the conviction that they [“the views

of the vast majority of contemporary scientists”] are not correct—that

in fundamental respects they are at best incomplete, and at certain critical

points demonstrably false, empirically. These are strong statements, but

our book will systematically elaborate and defend them".

Yes indeed,

these are strong statements, which basically translate as: “thousands

of scientists are wrong, we can prove it and therefore we are on

the right tracks and they’re not.” Is this an “uncharitable” reading, or

a “strawman fallacy”? Did I meet ST’s “challenge” here? I think so, but

perhaps that was a little bit too easy.

|

These techniques have yielded

a torrent of new information about the brain. Scientists and philosophers

confronting the mind-body problem even as recently as a century ago knew

only in a relatively global and undifferentiated fashion that the brain is

the organ of mind. Today we know a great deal more,

although our knowledge undoubtedly remains in many respects extremely primitive

relative to the brain's unimaginable complexity. We

know a lot about the structure and operation

of neurons and even lower-level constituents. We also know a lot about the

structural organization of the brain, its wiring diagram, and

thanks mainly to the new imaging technologies we have begun to learn a fair

amount about its functional organization, the manner in which complex

patterns of neural activity are mobilized and coordinated across spatially

separated regions of the brain in conjunction with ongoing experience and

behavior.

The empirical connection between mind and brain seems to most observers to be growing ever tighter and more detailed as our scientific understanding of the brain advances. In light of the successes already in hand, it may not seem unreasonable to assume as a working hypothesis that this process can continue indefinitely without encountering any insuperable obstacles, and that properties of minds will ultimately be fully explained by those of brains. For most contemporary scientists, however, this useful working hypothesis has become something more like an established fact, or even an unquestionable axiom. At the concluding ceremonies of the 1990s "Decade of the Brain," for example, Antonio Damasio (1999) encapsulated the prevailing view: In an effort that continues to gain momentum, virtually all the functions studied in traditional psychology—perception, learning and memory, language, emotion, decision-making, creativity—are being understood in terms of their brain underpinnings. The mysteries behind many of these functions are being solved, one by one, and it is now apparent that even consciousness, the towering problem in the field, is likely to be elucidated before too long (1). That an enormous amount of

methodological and substantive progress has been made by scientific psychology

in its first century can hardly be

denied, and I do not mean

to deny it. But what sort of

root conception of human mind and personality has so far emerged from all

this effort? There are many rapidly shifting cross-currents and variations

of detail amid the welter of current views, but to the extent that any provisional

consensus has been achieved by contemporary mainstream scientists, psychologists

and neuroscientists in particular, it is decidedly hostile to traditional

and commonsense notions and runs instead along roughly the following lines:

We human beings are nothing but extremely complicated biological machines.

Everything we are and do is in principle causally explainable from the bottom

up in terms of our biology, chemistry, and physics—ultimately, that is, in

terms of local contact interactions among bits of matter moving in strict

accordance with mechanical laws under the influence of fields of force.(2).

Some of what we know, and the substrate of our general capacities to learn

additional things, are built-in genetically as complex resultants of biological

evolution. Everything else comes to us directly or indirectly by way of our

sensory systems, through energetic exchanges with the environment of types

already largely understood. Mind and

consciousness are entirely generated by—or perhaps in

some mysterious way identical with—neurophysiological events and processes

in the brain. Mental causation, volition,

and the "self" do not really exist; they are

mere illusions, by-products of the grinding of our neural machinery. And of

course because one's mind and personality are entirely products of the bodily

machinery, they will necessarily be extinguished, totally

and finally, by the demise and dissolution of that body.

Views of this sort unquestionably hold sway over

the vast majority of contemporary scientists, and by now they have also percolated

widely through the public at large.(3).

They appear to be supported by mountains of evidence. But are they correct?

The authors of this book are united in the conviction that they are not correct—that in fundamental respects they are at best incomplete, and at certain critical points demonstrably false, empirically. These are strong statements, but our book will systematically elaborate and defend them. Our doubts regarding current psychological orthodoxy, I hasten to add, are at least in part shared by others. There seems to be a growing unease in many quarters, a sense that the narrowly physicalist contemporary approach to the analysis of mind has deflected psychology as a whole from what should be its most central concerns, and furthermore that mainstream computationalist/physicalist theories themselves are encountering fundamental limitations and have nearly exhausted their explanatory resources. The recent resurgence of scientific and philosophic interest in consciousness and altered states of consciousness, and in the deep problems which these topics inherently involve, is just one prominent symptom, among many others, of these trends. Even former leaders of the "cognitive revolution" such as Jerome Bruner, Noam Chomsky, George Miller, and Ulric Neisser have publicly voiced disappointment in its results. Chomsky in particular has railed repeatedly and at length against premature and misguided attempts to "reduce" the mind to currently understood neurophysiology. Chomsky (1993), for example, pointed out that empirical regularities known to 19th-century chemistry could not be explained by the physics of the day, but did not simply disappear on that account; rather, physics eventually had to expand in order to accommodate the facts of chemistry. Similarly, he argued, we should not settle for specious "reduction" of an inadequate psychology to present-day neurophysiology, but should instead seek "unification" of an independently justified level of psychological description and theory with an adequately complete and clear conception of the relevant physical properties of the body and brain—but only if and when we get such a conception. For in Chomsky's view, shared by many modern physicists, advances in physics from Newton's discovery of universal gravitation to 20th-century developments in quantum mechanics and relativity theory have undermined the classical and commonsense conceptions of matter to such an extent that reducibility of mind to matter is anything but straightforward, and hardly a foregone conclusion. Several contemporary state-of-the-art

surveys in psychology—for example, Koch and Leary (1985), Solso (1997), and

Solso and Massaro (1995)—provide considerable further evidence of dissatisfaction

with the theoretical state of things in psychology and of a widely

felt need to regain the breadth of vision of its founders, such as William

James. Solso and Massaro (1995) remark in their summing-up that "central

to the science of the mind in the twenty-first century will be the question

of how the mind is related to the body" (p. 306) and that "the self remains

a riddle" (p. 311). David Leary's (1990) essay on the evolution of James's

thinking about the self begins by documenting the remarkable degree to which

the Principles had already anticipated most of the substance

of subsequent psychological investigations of the self. He then goes on, however,

to emphasize that later developments in James's own thought—developments completely

unknown to the vast majority of contemporary psychologists—contain the seeds

of an enlarged and deepened conception of the self that can potentially secure

its location where James himself firmly believed it belongs, at the very

center of an empirically adequate scientific psychology. From still another

direction, Henri Ellenberger (1970) ends his landmark work on the discovery

of the unconscious with a plea for reunification of the experimental and

clinical wings of psychology: "We might then hope to reach a higher synthesis

and devise a conceptual framework that would do justice to the rigorous demands

of experimental psychology and to the psychic realities experienced by the

explorers of the unconscious" (p. 897).

notes: 1- This quotation and others in this book that do not list a page number were taken from sources published on the internet without specific pagination. 2- Newton's law of universal gravitation, insofar as it implies instantaneous action at a distance, appears to conflict with this characterization of physical causation, and indeed this feature greatly troubled Newton himself. The idea that matter could influence other matter without mutual contact was to him "so great an Absurdity that I believe no Man who has in philosophical matters a competent Faculty of thinking, can ever fall into it" (Newton, 1687/1964, p. 634). Newton himself presumed that this difficulty could eventually be removed—as indeed it was, more than two centuries later, with the appearance of Einstein's theory of relativity. 3- Just as this introduction was being drafted, a lengthy cover story on "mind/ body medicine" appeared in the September 27, 2004, edition of Newsweek. This article exemplifies throughout the attitudes I have just described, and it culminates in a full-page editorial by psychologist Steven Pinker, author of How the Mind Works (1997), decrying what he terms "the disconnect between our common sense and our best science." Pinker further advises Newsweek's massive readership that contrary to their everyday beliefs "modern neuroscience has shown that there is no user [of the brain]. "The soul' is, in fact, the information-processing activity of the brain. New imaging techniques have tied every thought and emotion to neural activity." These statements grossly exaggerate what neuroscience has actually accomplished, as this book will demonstrate. |

Let’s move

one. What follows is ST trying to explain how I misunderstand the “transmission”

hypothesis:

The

transmissive theory of mind-brain connection accepts a reciprocal interaction

between brain states and mental states. Normal perception is functionally

dependent on the brain, and this is consistent both with materialism and

the transmission hypothesis, because both of them accept brain causation

on mental states. But the transmission theory, additionally, offers room

to understand phenomena that materialism cannot explain (like the phenomena

explained in the IM).

Yes thanks,

that’s a helpful summary of what I was saying all along. Except that,

unlike ST, I find this whole thing ridiculous. Without the “phenomena

that materialism cannot explain”, which is again the very issue at stake

here, the “transmission” hypothesis is just a useless and maximalist (non-parsimonious)

way to interpret data (a bit like theistic evolution, or aliens commanding

humans to make crop-circles, or the more classic demon in the engine, if

you want). Moreover, it is misguiding to claim that the transmission hypothesis

accommodates without problems the findings from neuroscience. This is often

claimed in IM, but it is wrong. This is why I asked ST to explain basic

phenomena in terms of “transmission”, like binocular rivalry or synaesthesia,

and I could add data on split-brain patients, on semantic dementia, hormonal

modulation of affects and behaviour, and so forth. There is no simple way

for the “transmission” hypothesis to explain these things without turning

to ad hoc or fanciful explanations.

The result

is that ST and the authors of IM need the paranormal to be true

if the “transmission” theory is to be taken seriously at all. That’s a

first step, but even then, they are at a complete loss (as was Myers) to

describe it succinctly and to derive any experiment that could test it.

But of course, the evidence is so scarce, embarrassing and unconvincing,

as compared to the evidence for “materialism”, that believers prefer to

assume that it is amply sufficient and that scientists and skeptics simply

are unfamiliar with the relevant literature or prefer to look away. Of course,

they could simply do better research, find clear evidence, and publish it

in a scientific journal. But they prefer to think that scientists are a

nasty and dogmatic bunch (thousands of scientists around the world!),

as well as, of course, ignorant and/or fearful. This is not so far from a

conspiracy theory, and the scary thing is that I’m not so sure they would

take offense with such a comparison (after all, Donald Ray Griffin was well

into psychical stuff before he turned to his 9/11 whacko “theories”).

In

fact, the existence of such anomalous phenomena is so annoying for materialists,

that Dieguez has to use rhetoric and ridicule as an argument (what an

example of rationality!). Regarding Dieguez's use of rhetoric and ridicule,

he conceded in Michael Prescott's blog: "The “abridged

version on my pseudoscience shelf” was a rhetorical device to ridicule the

import of Myers, and to anger precisely those that see so much in him" Is that a rational argument? Is that kind of discourse

worthy of a Ph.D student? Is the use of a "rhetorical device to ridicule..."

a proper methodology of a serious and rational reviewer? I leave the readers

to decide that.

Well, I

can’t see why mockery and rationality are not compatible. However, reading

his comments, I certainly do now accept that being boring and gullible

are fully compatible. But I’ll also leave the readers to decide that. Furthermore,

it is worth reminding that we are talking about parapsychology and Fred

Myers here (and not about Mozart): mockery is de rigueur.

The

bottom line is that Dieguez has not presented any factual and rational

argument against the authors of ID. Lacking scientific arguments, he instead

resorts to the rhetoric, ridicule and other irrational fallacies.

That can’t

be the “bottom line”, because it wasn’t my point to present factual or

scientific arguments against the authors of IM (notice ST’s very interesting

typo here, he writes ID instead of IM). They wish someone would

start nit-picking stuff among their myriad pages, but what I did was more

appropriate, I think: I simply laid out what the book is.

So I have

reviewed the overall message and direction of the book in the restricted

amount of space I was given, and I gave my opinion about it. The goal was

not to debunk the contents of the book, but rather what it’s trying

to do.

Now ST

unearthed a comment I left on Prescott’s blog (itself referring to another

sentence I left on my own blog as a comment), to illustrate my smugness and

dishonesty:

Another

example of Dieguez's "rational and scientific argumentation" is this comment

in Michael's blog: "As

for the stance I hold regarding "debates" with believers of all kind,

it is true: I prefer a good laugh rather than a serious and useless fight."

If

Dieguez is logically consistent, he would have to laugh at believers in

materialism too (since his position includes "believers of all kind").

But the logical question is: is laughing a logical and rational argument?

Dieguez is so sure that his position is right that he can't deal with other

people opinions in rational terms; instead, he prefers to use ridicule,

ad hominem and other fallacies.

God this

is so boring. Do I really have to explain this quote of mine? Well, I’ll

give it a shot. I’m sure ST, and many other believers, must have realized

at some point that this type of debate as been going on and on for decades,

and that a simple discussion around one particular book will not settle

it at everyone’s satisfaction. So, why not lighten up a little bit and enjoy

our differences in a frank and relaxed debate? We know our respective positions,

right? We both think that the other is wrong, right? So let’s laugh

a little bit at the whole situation. And yeah, I laugh at “materialists”

too, on a daily basis as a matter of fact. I read scientific papers and

I very often exclaim things such as “there you go, we’re one step closer

to solving the riddles of the universe”. My snark is not unilateral, but

then one has to know me to be aware of this. I accept critiques along the

lines of “belief in promissory materialism” and so forth. The point is that

it doesn’t matter whether or not I’m “sure that my position is right”, what

matters is that I find no evidence in IM that my position is wrong.

One last

word about the use of ridicule: ST is the one who believes in GHOST STORIES,

not me. We nasty children love to mock such beliefs. One would think he

should be used to it by now.

After that,

ST takes issue with stuff I wrote about the authors of IM taking the success

of parapsychology for granted. They have an appendix listing books and

reviews on parapsychology (even reincarnation!), and whenever they make

a wild claim about telepathy and such, they refer the reader to it. ST

writes:

Their

point of citing the literature is to back up their assertions (therefore,

not arguing from ignorance!). But Dieguez, uncharitably (and intentionally?)

misrepresents the argument as suggesting we have to accept the literature

at face value. Another example of Dieguez's uncharitable reading and straw

man fallacy.

No, this

is not a strawman fallacy at all. The appendix on parapsychology is not

there to “back up” arguments at all, it was explicitly put there because

the authors do not wish to discuss parapsychology (or “psi”) in the book,

and so they merely say that they endorse this literature (although they

say it is “still controversial” and “imperfect” and that they don’t endorse

equally everything in it). This, in my book, is basically saying that one

should take paranormal superpowers at face value if IM is to make any sense.

Otherwise, psi and the appendix would not be needed for their argument.

ST then

jumps into another wagon and starts explaining why, if the evidence for

the paranormal is so strong, scientists do not accept it and do not even

care about it. I granted ST that if this could help him feel better about

himself, he could just go ahead and blame the nasty and ignorant academia.

Here’s his response:

Actually

materialism, naturalism, atheism and the fear of the "supernatural" is

responsible.

Yeah, that’s

what I thought. So it is a conspiracy (presumably, these same factors

are also to blame for the absence of creationism and astrology in the

classroom, therefore I’m soon expecting a documentary featuring IM’s authors

called Banished!).

To back

up this claim, which I granted anyway because I have no interest in this

particular brand of paranoia and self-aggrandizement so common in crackpots,

he quotes a “materialist philosopher”. This would be Thomas Nagel, grand

guru of mysterianism, which is enough said as far as I’m concerned (remember,

“What it is like to be a bat?”, that’s clearly the favorite paper of “materialists”).

Two more philosophers are then quoted, as ST loves arguments from authority

(I’m just hoping he didn’t extract the quotes from The Spiritual Brain—which

is essentially made of such quotes—, that would be most embarrassing).

But more generally, the idea that skeptics and scientists are “afraid” of

the paranormal is preposterous. Read my lips: “I AM NOT AFRAID OF THE PARANORMAL”.

See?

. God Damm it! Well, click this link and surely

you will be scared.

. God Damm it! Well, click this link and surely

you will be scared.It doesn’t

hold. Moreover, I’m not claiming around that believers in the paranormal

are afraid of materialism. That’s because I don’t have to, I’m content with

the observation that they have nothing to back up their wild claims.

But of

course, once one goes there, then everything is permitted and you can simply

say that your opponent is irrational for emotional reasons and draw this

nail further and further:

you

won't see such self-critical and honest concessions of the flaws of materialism

in a "Ph.D student" like Dieguez (whose best argument in favor of materialism

is that it hasn't been undermined by ghost stories!)

Read again

that last sentence in parentheses. Take a good look at current science

and its astonishing successes, its continuous progress in numerous fields,

and ask yourself why it works so well despite the existence of GHOST

STORIES. I know I’m repeating myself here, but the overall resistance of

science to the supernatural is indeed a perfectly valid argument for

materialism. Again, you can imagine how the world and life should

look like if all of IM were true. Instead, what we find over and over again,

is that isolated and bizarre “paranormal” events are always just ambiguous

or controversial enough so that they turn out to be entirely irrelevant

for a sound understanding of reality (but still allows the believer’s will-to-believe

to keep rolling).

ST then

quotes from Hyman’s assessment of the SAIC experiments, which is clearly

off topic here (but then ST likes dropping names very much). I don’t care

about this particularly embarrassing phase of parapsychological research

at SRI, which has utterly failed to provide evidence of anything paranormal,

again. I’m annoyed, however, but not surprised, by the tendency to cherry-pick

a few appeasing sentences by Hyman in an otherwise wholly negative assessment

of a project that was aimed at training super-heroes. What ST fails to

notice, interestingly, is that Remote Viewing, which was the topic of the

SAIC project, is not addressed at all in IM. Why?

Thankfully,

what follows is funnier. Remember that ST confronted me with a video where

Michael Shermer, a skeptic, found evidence supportive of Vedic astrology

in a non-scientific televised show. ST is of course unable to perceive

the ridicule of this whole situation, but I enjoy it a lot. So I said:

yeah sure, go for it, Vedic astrology is for realz because Shermer, like,

proved it, you know. And I added for good measure that I found unforgivable

that Vedic astrology is not mentioned in IM at all (by the way, how does

the “transmission” theory accommodate with astrology? We might never know).

But here’s how ST reads all of this:

This

is an amazing concession. According to Dieguez, Michael Shermer found

evidence for vedic astrology! And he concedes that "So

yeah, it totally seems that thanks to the science of Vedic Astrology,

one can approximate some individual's personal features merely by knowing

his or her date and place of birth"

(My God, I'll be referring to this "skeptical" concession all the time

in this blog! By the way, note that Dieguez doesn't admit any consequences

for materialism and mainstream science by his concession of positive evidence

for Vedic Astrology. This will give you an idea of the logical coherence

of Dieguez)

Yes, write

it down, Sebastian Dieguez accepts the evidence for Vedic astrology, as

he is entirely devoted to whatever Michael Shermer says or does, and believes

that 10 minutes long TV shows are better than real scientific reports.

So you can quote me all you want on this: VEDIC ASTROLOGY IS TRUE (although

I don’t even know what it is). I now demand that “mainstream” neuroscientists,

as well as the authors of IM, stop immediately their misguided

ramblings, and devote themselves to this venerable science. Which raises

the question: does ST actually believe in Vedic astrology? And does he

think that Shermer is to be trusted when he finds evidence for crackpot

notions, but not when he debunks anything else?

I enjoy

this so much that I will go one step further. ST asks:

My

question for Dieguez is: Do you consider the evidence (gotten by skeptic

Shermer) stronger than the evidence for psi (e.g. as explicitly conceded

by Ray Hyman)?

Yes, I’m

happy to concede this. Again, I am now a full convert in Vedic astrology,

all the rest is utter nonsense. Tomorrow, I will talk with my thesis advisor

and present him with Shermer’s video. If he doesn’t allow me to switch

my topic on the spot to Vedic astrology, I will resign immediately and

move to India. So there.

What follows

is more whining about my attitude and about the sin of “debunking”. This

is only more literal reading from ST, who gets very serious with skeptics

but all mellow with certified nutcases like Denyse O’Leary. There’s nevertheless

something funny coming, after ST quotes some of my ramblings about the

paranormal and how I characterize it as GHOST STORIES:

Ghost

stories again...? Man, it's impossible to argue with a person who cannot

discern any difference between telepathy, psychokinesis, NDEs, stigmata

and even mediumship from "ghosts".

Because

of course, it’s much easier to discuss with someone who actually

believes in ghosts, as well as GHOST STORIES. Anyway, something more interesting

comes after this, where ST dismisses my argument that IM relies in many

places on the explanatory gap and the naïve folk psychology of free will.

He says that this is irrelevant:

The

question is whether materialism can account for free will or not, and

if its implications are morally acceptable or not.

This misses

the point badly. My concern is not about morality, but about the naïve

conception that volition and consciousness somehow pre-exist to brain processes.

The extended quote from Keith Augustine is interesting but totally irrelevant

in the present context. But it gets even more confused:

It

is irrelevant whether most people believe in objective moral values or

not; the point is that materialism and naturalism cannot account for them.

Materialism

cannot account for free will and morality? Ok, so please feel free to

never attempt to do any science on these topics. You would not be helpful.

Then, inevitably,

because I said that free will and consciousness are “illusions”, ST is

more than happy to explain to me how I defeated myself with such an assertion

(like I never heard that argument before):

That

comment is self-refuting. If consciousness and thinking is an illusion,

then your arguments (which are based on ideas in your consciousness) are

illusions too. And we can't predicate the values of "truth" or "falsity"

to illusions, because our own conceptual adjudication of such epistemic

and logical values would be an illusion too. You can't defend your data

on rational grounds, if previously you concede that your own mind is an

illusion. You're using an illusion (your consciousness) to justify another

illusion (the scientific data obtained by the illusory consciousness of

scientists).

Very well

done. The problem is that my illusions actually seem to match the real

world and help me navigate in it and make sense of it in an honest and

humble way (i.e., I don’t think that the purpose of the universe is all

about me). And I can also make predictions that work out. On the other hand,

ST seems to imply that naïve realism is actually a viable option and that

he is not prey to the constructive, anticipatory, pattern seeking

and interpretative processes in his brain. Good for him, that will certainly

help him understand how the mind really works.

Let’s turn

now briefly to NDEs, a favorite topic of mine. That’s about the only direct

reference to the contents of IM that I actually made in my review: I dismissed

the argument that NDEs are “paradoxical” in the sense that they provide

evidence of “enhanced cognition” during a time where the brain is not supposed

to be able to support such mental processes. I simply replied to this along

these lines: if dysfunctional brain activity cannot account for the type

of experiences lived during a NDE, why should no brain activity at all

be a better explanation?

Here’s

what ST responds:

Because

if there is no "brain activity at all", how the hell are you going to

have mental experience? If the mind is a product of brain functioning

(like materialists like Dieguez think), then the mind ceases to exist when

the brain ceases to function. It's a purely logical point, and it is amazing

that Dieguez can't see it. If you don't have any brain functioning, how do

you explain the mental experience had during that period?

I’m not

sure how to put this without sounding too harsh. Let’s try this: ST simply

missed the point.

The authors

of IM, and also Parnia and Fenwick, do not claim (unlike many other believers)

that NDEs occur while the brain is entirely shut down (or “flatlining”).

It seems that they have carefully read the data, they even have finally

opened Sabom’s book and actually read the Pam Reynolds account, and they

came to the conclusion that there is no such evidence at all.

Rather,

they try to be more cautious and say that during cardiac arrest NDEs, the

brain endures such pressure that it must not be able to form clear concepts,

memories, etc. This simply begs the question, of course, for no one knows

when an NDE occurs exactly (except when some external stimuli is

incorporated in the hallucinated scene, always when the brain is working),

and no one knows what happens in the brain during an NDE anyway. Moreover,

as the authors of IM make clear in their book, we don’t even know for sure

what type of brain state we should deem able or unable to support mental

processes in the first place. So my point was: if they grant that the best

one can say about NDEs from a paranormal perspective is that they occur during

states of brain impairment that are not compatible with consciousness and

memory formation, then why should no brain activity at all be de facto

a better explanation?

Why not

accept that in some cardiac arrest patients, the brain impairment, or the

brain recovery allowed by CPR, is such that it precisely produces very vivid

vestibular and visual hallucinations? After all, we already know that

brain disorders produce NDE-like experiences, don’t we?

Ok, here

I skip some further misconceptions and circular reasoning from ST, in

order to stay in the NDE domain. Here’s what I wrote in my response to

his previous post: “If NDEs are a peek in the afterworld, I don’t see

why only a tiny minority of cardiac arrest survivors report them, and I

don’t see either why so many who report them were actually not near-death

at all.” And here is his response:

Because

those who report them have been detached from their bodies, and such separation

occurs only occasionally, not constantly in each person. This is why most

people don't experience a NDEs (and this is what we would expect if the

IM arguments are true).

I don’t

even know where that comes from. It would be good if ST could explain

how it is not circular to claim that those who had an NDE where separated

from their bodies, while those who had no NDE were not. Also, one wonders

why this process should occur only “occasionally”, and on what grounds,

if NDEs really are what believers think they are. Moreover, I can’t see

why this vindicates the “IM arguments” in any way. But maybe ST, like me

right now, is getting a little bit tired.

He then

proceeds to some question begging about how “psi” exists in everybody

and not only in “psychics”, is therefore all over the place, and comes

in different intensities because it’s just like any other human skill.

How does he know all that? He doesn’t say, but refers me to a book by

Dean Radin, the man who explains on his blog that skeptics are to blame

for witch burnings.

Of course,

he says that none of this is begging the question, but “an inference from

the data”. I don’t want to aggravate my case as a failed PhD student, so

I will refrain to take this particular point further (suffices it to say that

no, psi is not all over the place, deal with it).

So, let’s

now turn to the final points. I really want to know what scientists like

me should do if everything in IM turns out to be true. So I asked: should

I become a parapsychologist? If not, what should scientists do?

Here ST wants to sound reassuring (after all, we scientists are paralyzed

by fear, so we need a little patting on the back from time to time):

They

should develop models of mind-brain connection that are consistent with

all the data. Actually, the IM book tries to give some ideas (e.g. regarding

the transmission theory) to account for the data. It doesn't mean that

the transmission theory is correct, or the only alternative; the point

is to think of alternative models to understand the mind-body connection,

in a way to account for all the known phenomena (including the "anomalous"

one, which cannot be accounted for by materialism, and have to be dismissed

by the use of ridicule, rhetorical devices and speculations about ghosts

stories)

Good. I

can give some recommendations too: show us good evidence that we need

an “alternative model” at all (not rogue phenomena or “bundle” of useless

sticks, just good data please), then work out a clear theory, make predictions,

make new experiments, publish them, and so forth. Also, dig in the neuroscientific

literature and explain why an “alternative model” would make more sense

of the data. When you’re done, publish another book in yet another century,

with an enclosed CD of Irreducible Mind in it. If I’m still around,

I’ll be glad to review it.

We’re near

the end. ST thinks that I’m now so tired and devastated by his arguments

that I can’t see through his pathetic attempt at shifting the burden of

proof. I merely explained that the “transmission” theory, by the own account

of IM’s authors, is not clear at all and demands further theorizing. That’s

where they introduce my favorite lines of the book, when after some 800

pages

they say

that the theory that will lead to a new psychology for the 21st

century is not yet available, but will be the subject of another book

as soon as it is worked out. So I’m not the one who has to explain why

the theory is empty here. There simply is no theory, just a vague

reference to the Victorian musings of bearded men that had no TV and sought

amusement in séances, plus the familiar quantum obfuscation. But then ST

is deaf to all my noise, and merely observes:

My

point is that a rational review should specify the objections to the theory

being addressed. Asserting that the concept is empty, or that the authors

make many false claims is not an argument, if you don't back up your assertions

with evidence.

One has

only to read the following sentence to see how he rejects my characterization

of IM as a “soul of the gaps argument”:

The

transmission theory is not the "soul of the gap argument". It's an hypothesis

that tries to account for phenomena that materialism cannot explain.

ST obviously

spent too much time with Denyse O’Leary: he now talks like ID creationists

(can it be a coincidence, or even a “meaningful coincidence”, that the

term “irreducible” is used in the same way by Kelly et al. and by creationist

Michael Behe?).

So let’s

turn to the conclusion:

In

my view, Dieguez has not understood the IM book. His failure of understanding

is a result of his prejudices, conceptual confusions (e.g. telepathy =

ghost stories), ignorance of the flaws of materialism, logical inconsistences,

and emotional attachment to his worldwiew.

In

any case, maybe this exchange will help Dieguez to reflect and reconsider

some of his positions (even though I doubt it will happen).

ST is mistaken

here. I learned a lot thanks to him. I am now a proud believer in Vedic

astrology, has he forgotten?

In our

next installment, I will turn to more interesting comments by another critic

of mine, Julio Siqueira. Expect more of the same and a lot of repetitions.